August’s Featured Catch: Chilean Seabass

Who are you calling a Patagonian toothfish?! Meet the flavorful fish with the catchy alias.

Jul 24, 2025

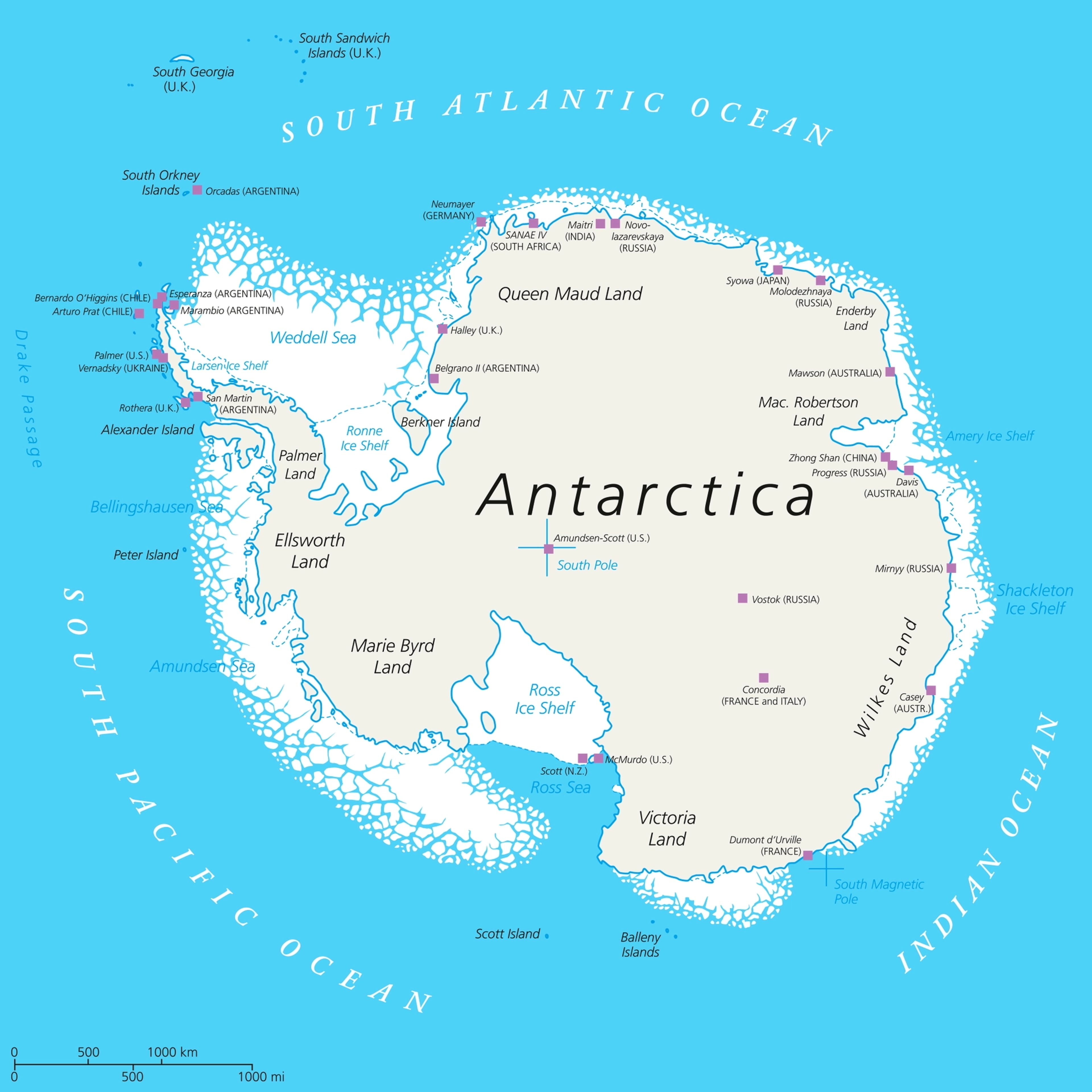

Few proteins have taken such a long, strange trip to the plate as Chilean seabass. The delicious, buttery white fish is harvested in the rough seas between South America and Antarctica, about as far away from the United States as you can get without leaving the Western Hemisphere. But the most unusual aspect of Chilean seabass isn’t its remote origin — it’s that it’s not even a true bass!

For starters, the Chilean seabass is not one fish but two. The Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) and the closely related Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) are both sold under the name Chilean seabass. American seafood merchant Lee Lantz is credited with renaming the fish after tasting the Patagonian toothfish in Chile in the 1970s. The gambit worked: This menacing-looking fish, with ruddy skin and sharp and oddly configured teeth but also smooth, white flesh, became incredibly popular, leading to what the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) refers to as “the white gold rush” in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

From overfished to sustainably fished

Here’s where the story takes a dark turn. The thick, white fillets sold as Chilean seabass excited chefs and consumers alike, leading to a surge in demand, and then in price. Illegal fishing of the toothfish ran rampant, and by the 1990s, the Chilean seabass had become the poster child of overfishing. According to the MSC, the supermarket chain Whole Foods stopped selling it and hundreds of chefs in the United States joined environmental groups in urging consumers to avoid it.

Pirate ships camped out in South Georgia near the Falkland Islands and in the Ross Sea off of Antarctica. They were not only scooping up toothfish illegally, but carelessly harming sea birds and other marine wildlife in one of the most remote parts of the world.

Fortunately, the MSC — along with the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), environmental groups, and fisheries — fought back. The CCAMLR, a coalition of 25 countries charged with conserving fish resources in the Antarctic waters, set catch limits and established other sustainability and traceability measures. Another organization, the Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators, even partnered with eco-vigilantes to prevent illegal fishing of Chilean seabass. The first MSC-certified fishery was created in South Georgia in 2004, and the first in the Ross Sea came 10 years later. By 2016, the poachers and pirates were eliminated from the toothfish habitats, and companies like Mark Foods, which sources from MSC fisheries in South Georgia and the Ross Sea, can now provide sustainably caught Chilean seabass to consumers and chefs.

To catch a fish

It’s not easy to reel in Chilean seabass. Videos on YouTube of boats fishing the Ross Sea rival scenes from the long-running crab fishing docu-series Deadliest Catch, with rolling waves and ice floes.

A fishery vessel takes about three weeks to get to the Ross Sea from South America for the season, which runs from December to February. The boats, according to this video from Mark Foods, are about 160 feet, have a crew of 23 plus two government observers, sail “often in extreme weather."

The crew sets long lines that can stretch 7.5 miles with 3,000 to 5,000 hooks baited with squid to attract the Antarctic toothfish, which weigh between 60 and 80 pounds. The lines are set at depths where the fish are known to inhabit, typically between 300 and 3,500 meters (1,000 to 11,500 feet). The crew employs tactics such as using fast-sinking lines to minimize the risk of injuring sea birds, while the hook design for catching Chilean seabass intends to minimize bycatch, or other types of fish.

Another fishery that Mark Foods employs is in South Georgia, in the South Atlantic Ocean, with a season that runs from April to August. Here, the Patagonian toothfish are caught using longlines as well, though the fish are smaller, roughly 15 to 20 pounds each.

In both fisheries, the fish are brought on board and immediately processed. This includes gutting, cleaning, and sometimes fileting the fish. The fish are then blast frozen at very low temperatures and then stored at 13 degrees Fahrenheit until delivery to distributors such as Vital Choice.

A long journey to the plate

The ability to responsibly source Chilean seabass is a game changer in the kitchen. With white, tender flesh that looks like the best wild cod or halibut, this fish is somehow more velvety in texture than either and has a smooth, clean flavor of its own.

Cooking Chilean seabass is simple. Prepared with salt and pepper, it can be pan-seared with butter and fresh herbs. It takes well to a variety of sauces in the pan or can be topped with complementary last-minute additions like artichoke-lemon pesto.

Chilean seabass lends itself well to experimentation, or you can recreate inspired recipes such as Chilean seabass with avocado mash and citrus fennel salad; cherry tomatoes and herbs; or even grilled and served in tacos.

While it’s the central ingredient to an unfussy main course, the Chilean seabass is a sophisticated protein that calls for a proper wine pairing — almost exclusively with white wine. Try a light and crisp Oregon pinot gris or a medium-bodied chardonnay. If you must, a nice rosé or flavorful Pacific Northwest pinot noir can also pair with Chilean seabass.

No matter what you call this fish, Chilean seabass should be on your plate at dinnertime.